Google have never built a good tablet. It’s a shame, because however good the iPad has become it needs competition to be great. The closest competitor is the Surface, but it is only recently that Apple and Microsoft have converged: Apple turning the iPad into a primary computing device, and Microsoft bringing the entry level surface to sub-£400. There is a gap in the market. For Google.

2011 looked promising for Google. It had been a year since the announcement of iPad and Android 3.0 Honeycomb was the future. A whole OS designed specifically for tablets. A .0 release and an all new user interface. Google weren’t just bolting on tablet support, rather committing to next generation devices.

The Motorola Xoom launched as the first tablet to run this OS and it was fine. It had a larger, higher resolution display than an iPad 2, a flashy Nvidia Tegra 2 and double the RAM than Apple could muster. It had a Super Bowl Commercial. It had PC World calling it ”the most polished Google software effort to date”. In many ways, said Joshua Topolsky, then Editor in Chief of Engadget, it ”outclasses the iPad”.

Then within two years, Google released Android 4.2 and killed the tablet interface with it. And the Xoom became just a small hint at what could have been.

Because Google had just released the Nexus 7 that put the same power as an iPad with the same resolution screen as the Xoom in the palm of your hand. For £159.

Google’s strategy turned to price. Provide better value than the iPad and a more comfortable reading experience. In a time when average screen size for a smartphone was only just crossing 4”, the Nexus 7 was certainly a tablet. Android was well suited to a larger portrait device, having ditched the landscape-first elements that made the Xoom look like a serious iPad competitor.

The Nexus 7 sold up to 4.8 million units in 2012, over 10x that of the Xoom’s first 3 months on the market.

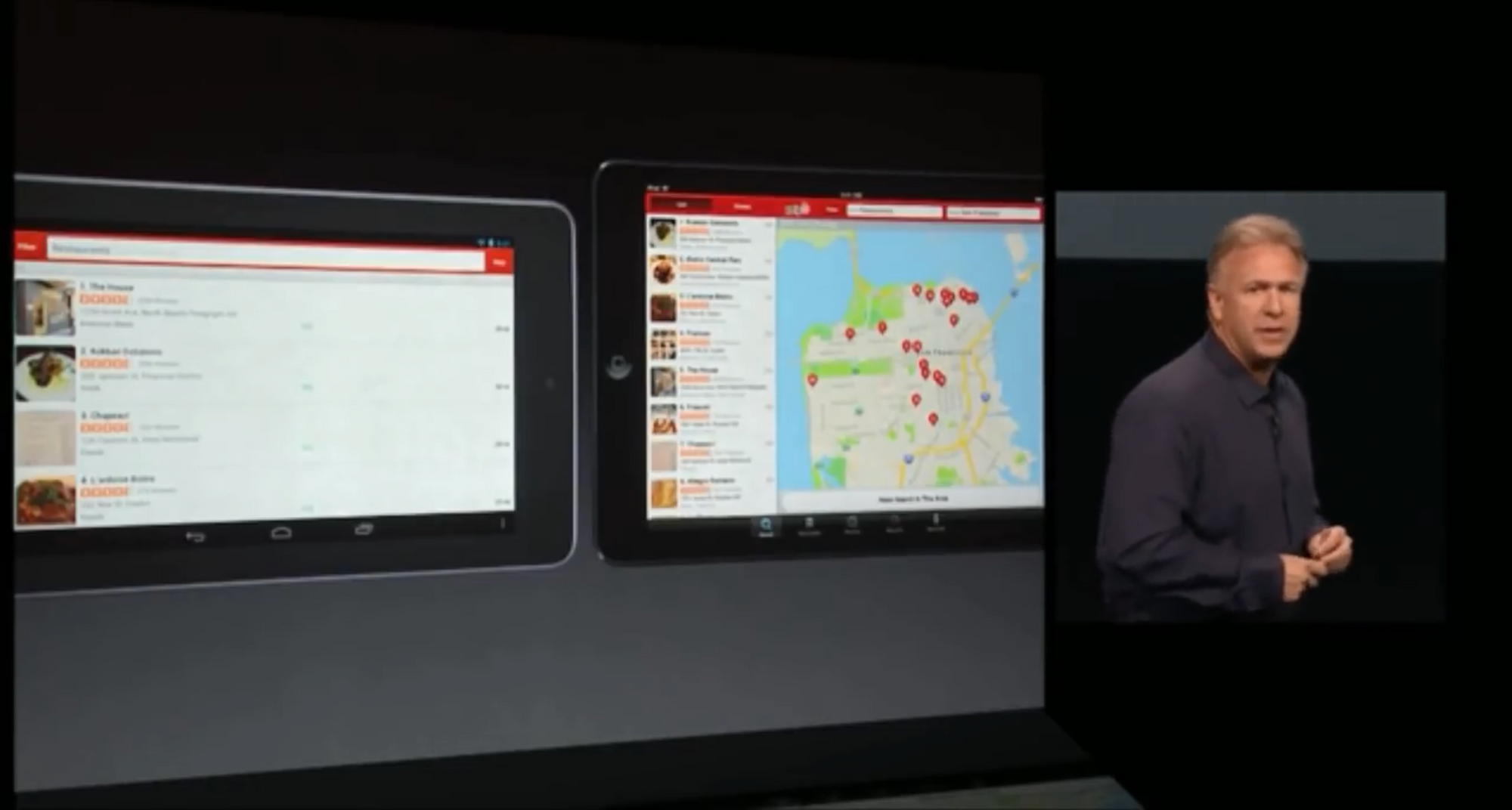

Even Apple reacted. They launched the iPad mini to compete directly. They put it side by side with a generic Android tablet clearly designed to represent the Nexus 7 to show why Apple’s design decisions were the right ones.

Apple went hard with their criticism of ”phone applications stretched up” comparing to their tablet optimised interface with Android post-Jelly Bean. But those buying the Nexus 7 did not care.

Those buying the Nexus 10 did.

Alongside this success, Google had launched a larger device, the Nexus 10, that sold less than a million, and served as a signal that Google didn’t understand why the iPad was successful.

Perhaps it was always doomed when Matias Duarte, who now is the VP of Material Design at Google, introduced this Samsung built device as a “beautiful piece of plastic”.

When asked about the software, what made iPad great, all Duarte could say was that the Nexus 10 was thin, light, and had a high resolution display. He said that as long as developers built apps for Nexus 7, they would have apps for the Nexus 10. While technically true, clearly, an app designed for a 7” display is not immediately a good app on a 10” one. The Verge, unsurprisingly, would later report the ecosystem to be ”woefully lacking in tablet apps”.

Reviews, though, were generally good. The display was ”fantastic”; it was more pixel dense than Apple’s Retina display iPads, with a “very capable processor” putting the device on the ”cusp of something amazing.”

So why did it fail? Not because the iPad was that much better hardware. Even the Surface, that still exists today, was selling at a slow pace. The question remained: why buy a Nexus 10 when Google are not serious about coaxing developers to optimise for it?

It took the Nexus 10 two years to get a predecessor and in that time little was done to incentivise Android apps to work better for larger screen sizes. The Nexus 9 was more expensive than an iPad, had poor performance, and ran apps from developers who had completely given up on tablet counterparts. When iFixit opened up the device, they called it an “exercise in corner cutting,” a wise summation of Google’s continued lacklustre tablet efforts.

And so to the modern day. For the most part, there are no mainstream Android tablets. There is the iPad, and there is the Surface. The best, low-cost alternatives to these have for a while been Chromebooks, which are superb for education. It therefore seemed like a sensible decision for Google to announce the Pixel Slate, the first ChromeOS tablet.

For $799.

On the surface it was a good device, with a high resolution screen, betterexternal display support than iPadOS, more claimed battery life than the iPad, and it ran Android apps.

The reality did not match. The software was poor, and videos showed it performing extremely slowly. MKBHD posted an uncharacteristically harsh review of the device, entitled: “This Ain’t It Chief.” “This thing has made me so sad,” he began, before showing up scaled phone apps lag their way through simple operation.

Despite a great display and speakers and two USB-C ports, Google agreed with the press. They cancelled the project and with that Google-made tablets were dead.

So what is the future? Unfortunately, there probably isn’t one. Google have time and time again demonstrated that they don’t care enough about fostering great tablet software experiences. There will be attempts to make more hardware from OEMs like Samsung, but there is very little incentive when Google are not focussed.

Our best hope for a good Google tablet is a modern day Android Honeycomb, a rethinking of Android that encourages developers to adapt for the larger screen. We know Google are capable of good hardware and capable make a compelling iPad competitor, not for $799, but for the price of an iPad. They just need apps.

The iPad is a great device. But it could be better with more competition. Competition that I wish would come from Google.