When I was a teenager, I used to trawl the internet for hours to find torrents of indie apps. Most of the time they were apps I had no use for, powerful productivity tools completely unsuited to a high schooler.

But this was as age before the iPad Pro, before the Mac App Store, when software seemed expensive. It was expensive even compared to today when the app I write on, the app I schedule with, my notes app, to-do lists, even ironically, my budget tracker all total three figures worth of subscriptions.

This norm of 2020 is a source of much anger and despair from normal people not like me. It is anger that only grows stronger when it becomes easier and more economical for developers to support multiple platforms under a subscription. The same people who would once spend £2 on coffee but not 59p on an app, are now the people who claim they’d rather pay £50 for a download instead of £30 a year.

And while financial arguments for subscriptions are well understood — indie developers need to earn money on a recurring basis in a competitive market on an anti-competitive app store — the feeling of being trapped in a money sink is not pleasant for anyone.

It’s especially unpleasant when apps remove features for their existing paid users when they shift to a subscription model. It was painful when adverts began appearing in Twitterrific, even if you had previously paid. Perhaps the biggest secret to launching a successful subscription model, is how developers treat their loyal customers.

The most loyal users — the true fans of an app — may be happy to pay more for new features, but others suddenly have an inferior app. For Twitterrific, only users who hadn’t paid in the five years preceding the subscription’s launch would see banner ads. But ads on a paid app made headlines even if the app now receives more timely updates that its upfront purchase competitor: Tweetbot. Adding banner ads did still seem antithetical to App Store head Phil Schiller’s mission to “reward” developers who “do a lot of work to retain a customer over time”.

When Fantastical moved to a £39/yr subscription, users on Reddit lambasted the company for killing “all the goodwill [they’ve] built up over the years,” threatening to uninstall because of the “sad” and “ridiculous” paywall. But if anything, Fantastical is the perfect example of a subscription app. It’s an app that uses completely portable third-party services. You don’t lose anything when the subscription expires.

So it felt worse when apps like 1Password started charging a yearly fee because by design it contains users’ most important data in a proprietary format. But despite hiding it wherever possible, they did continue to allow one-time purchases separate to their sync service until very recently. They also stopped charging individually for different device installs. And they know that once you are a happy 1Password customer, you are paying a subscription for life.

Many of Apple’s own policies are guilty of both encouraging subscription apps and fostering hate of them. Developers are incentivised to use a subscription model because if a customer subscribes for more than a year, Apple halve their App Store fee from 30% to 15%. This also ensures Apple’s continued income from the store.

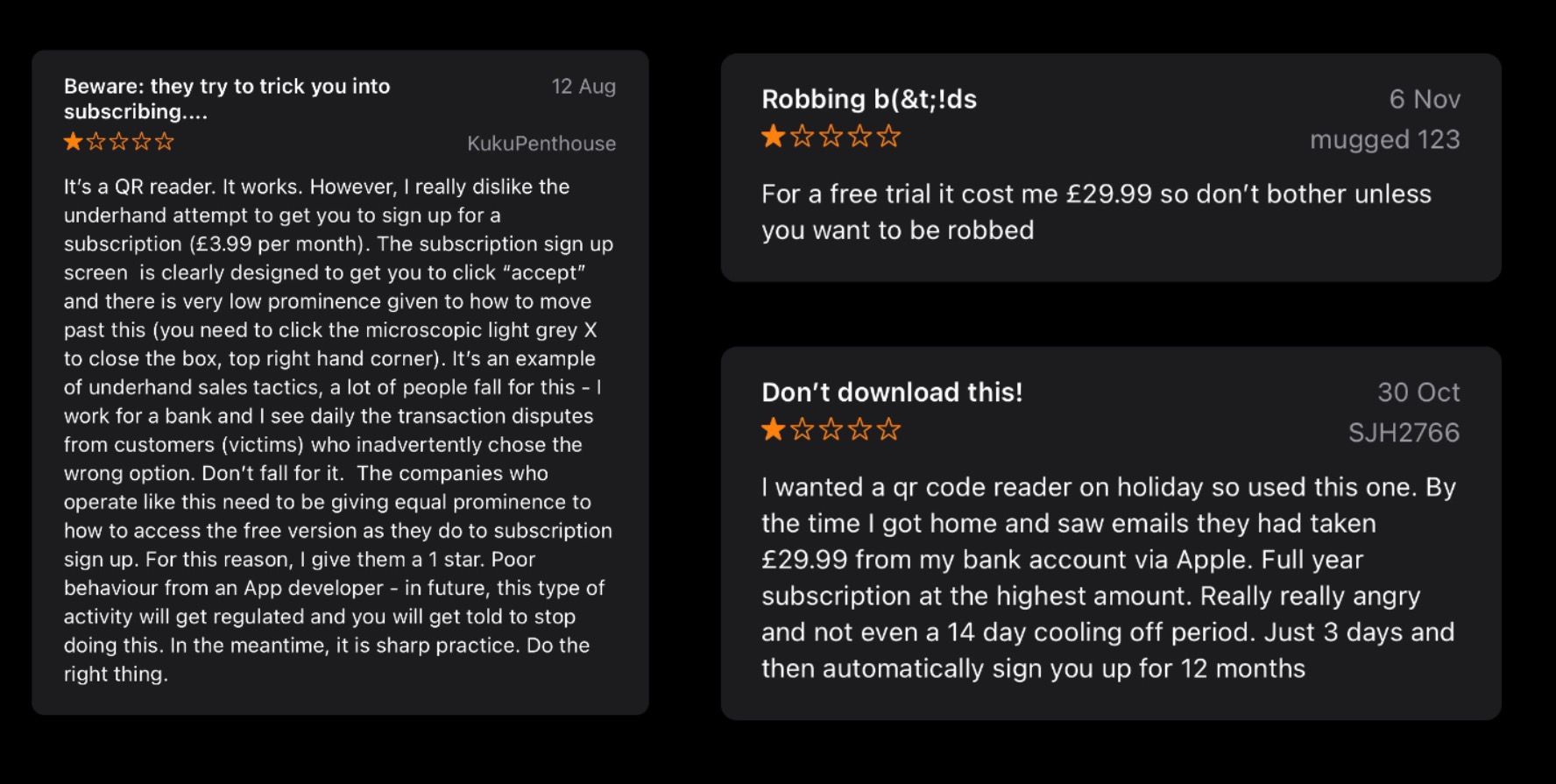

Unfortunately, Apple have also allowed, and show no sign of clamping down on, scam subscriptions. One QR code reader was allowed on the App Store for long enough to earn an annual revenue of $5.3 million. How? By tricking users into a 3-day trial before maturing to a $156 a year subscription. This app is still live, if cheaper, and still scams people today for a feature that exists for free in Apple’s own camera app. One user found bogus virus scanners charging $99 a week, and a VPN with fake reviews in the top grossing apps chart.

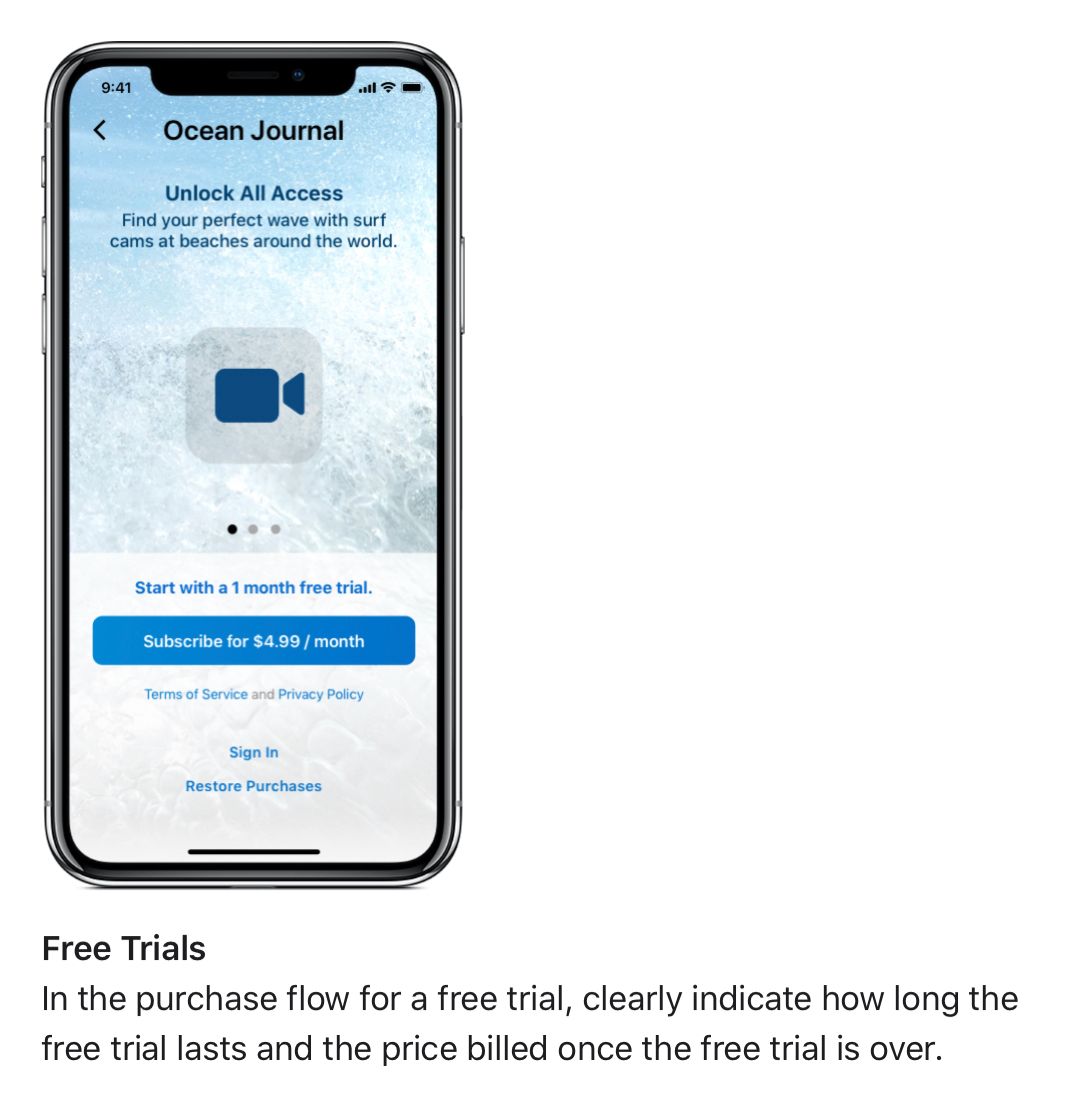

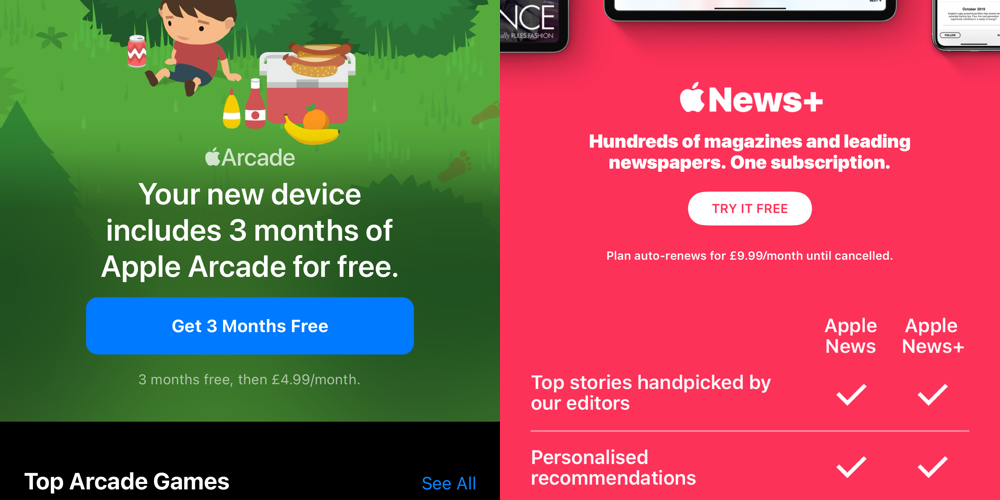

Apple profit from this and therefore have little incentive to remove such apps. They do have some policies to discourage it, but Apple themselves break them. Their developer guidelines show clear examples of how to display subscription pricing inside a button, but in Arcade and News+, they hide pricing in tiny text under leading button labels pushing you to ‘TRY IT FREE.’

If they can weed out such scams and respect developers with one-time purchase fees, perhaps Apple broad and aggressive moves towards making everything they do a monthly fee would be more palatable when they offer value. The iPhone Upgrade Program is essentially a monthly subscription for a phone with frequent updates. And Apple One thrives on users being tied to Apple for their entertainment and fitness. Maybe one day they will combine.

It wouldn’t be a terrible thing because over the past year, I’ve been more and more happy to part with a recurring fee for products I like. With a subscription, I get apps on all my devices in one go, instead of having to choose what devices are most important to me. There are constant updates; the apps I subscribe to were the first to get widgets on iOS 14 and redesigns for macOS Big Sur. Some apps even give you the base app forever but only provide updates if you are subscribed. And with platforms constantly evolving and new devices and paradigms surfacing, from trackpad support on iPad to AR glasses, paying for a static piece of software isn’t going to serve me in the long run.

Even when we don’t want an app forever, those that have portable data can be trialled for pocket change month by month, allowing us to explore all the different alternatives in the store for the same price as buying one large download we might not even use.

And every indie app I mentioned here I already pay for. And I love them. Because with some work, we can make the app store exciting again. We can bounce across innovations and embrace motivated developers. Subscriptions are here to stay, and I can’t wait to see what the next generation of indie app creatives can do with the incentive.